Loss Of An Icon

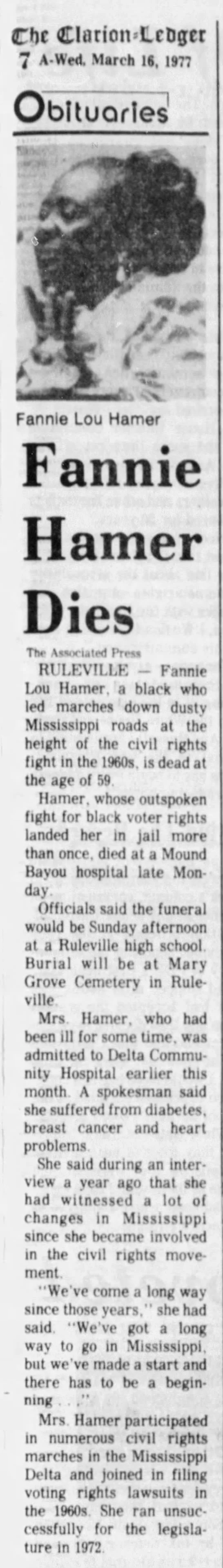

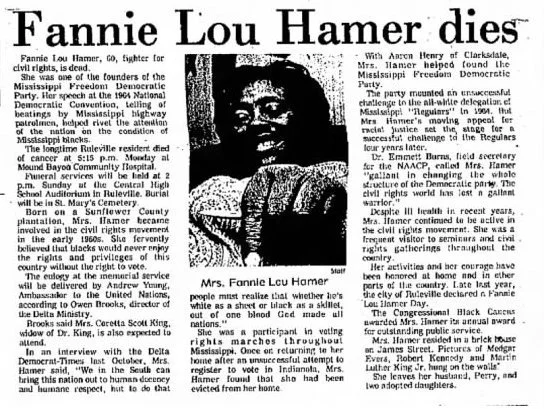

Monday, March 14, 1977

Hamer’s life had been a long, hard road. Photo by Louis Draper and courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Signs of Hamer’s failing health were evident in one of her last television appearances on Black Leaders 1973 hosted by Tony Brown.

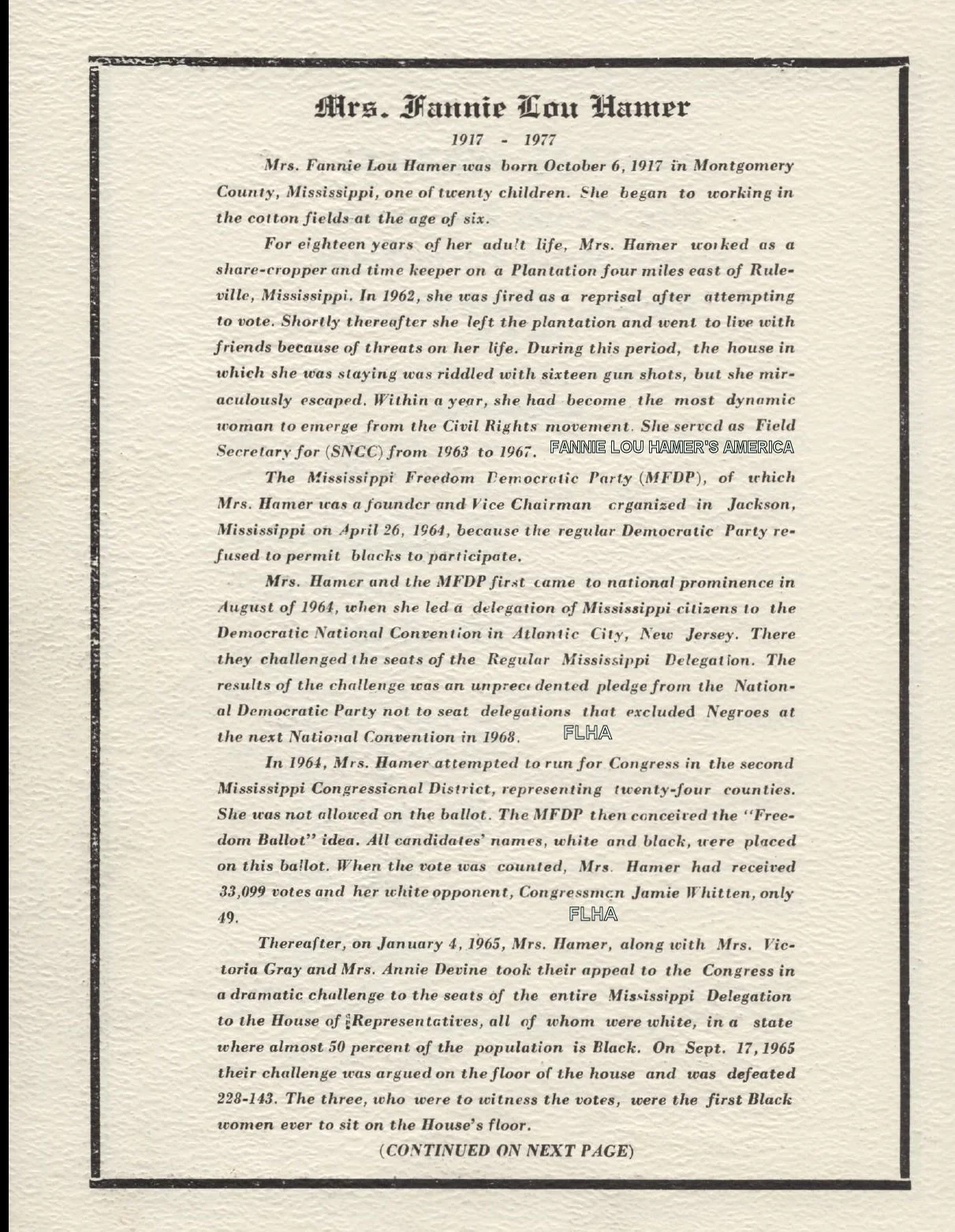

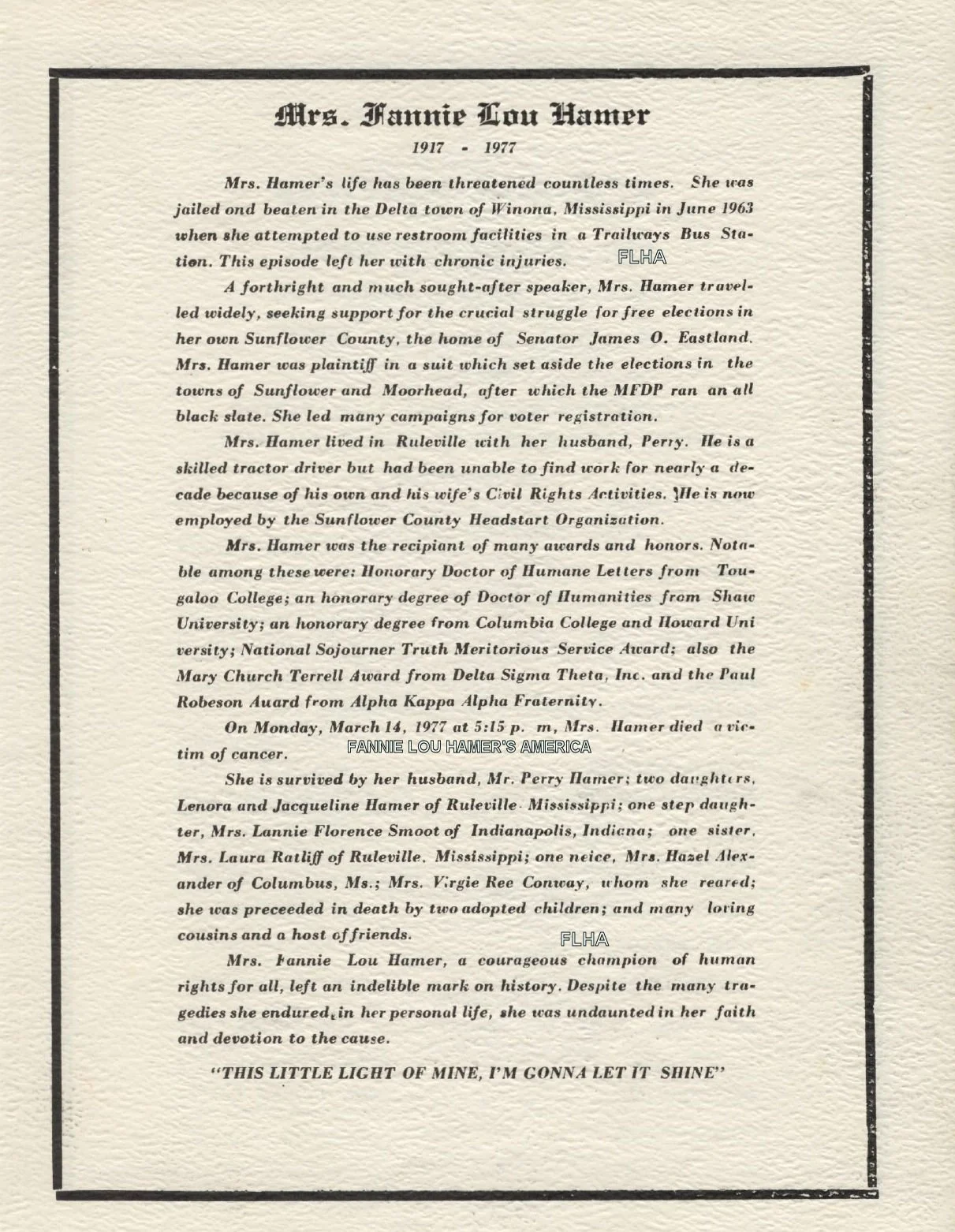

Always the consummate advocate for one cause or another, Fannie Lou Hamer’s highly physical and emotional mission was finally taking its toll on her. As the fall of 1971 turned into the winter of 1972, Hamer slowly began to withdraw. She had long suffered from the effects of the savage beating she received at the hands of law enforcement officials in a Winona, MS jail cell. That assault left her with permanent kidney damage, backaches, headaches, and severely compromised eyesight. But the pain and exhaustion she experienced during the last winter months suggested that something else was wrong. The unbearable physical pain combined with psychological worry - rooted in a lifetime of trauma - kept Hamer up at night and in bed most of the day. Then one afternoon in late January 1971, cold sweat trickled from her forehead as she squinted against the winter sun’s glare. She had organized a boycott of a local store where the owner had kicked a young Black girl in the back. The boycott had gone on for two weeks, and Hamer supported her Black community in Ruleville in the boycott and demonstrations, despite the fact that she grew weaker and dizzier day by day. Suddenly, the picket line chants faded into the background and her legs became numb. Fannie Lou Hamer slowly fell to the pavement with her fellow demonstrators rushing to her side. Tattered handkerchiefs mopped her soggy brow. Concerned faces crowded her vision. Her husband, Pap, soon arrived and took his wife to the Tufts-Delta Community Health Center in Mound Bayou, MS. Her heart rate slowed down a bit, and she was finally able to take deeper breaths. Pap wheeled her inside where she was examined by a doctor. In the midst of their panic, Pap and Fannie Lou Hamer tried to focus as the doctor explained to the shaken couple the symptoms of nervous exhaustion. The medical professionals ran tests and listened carefully as Hamer described her fatigue, blurred vision, aches, pains, and feelings of frustration, hopelessness, and despair. Running her beloved Freedom Farm; campaigning for the State Senate; traveling and speaking nationally, while caring for, Jacqueline (Cookie) and Lenora (Nook) - then just five and six-years-old was wearing her down. Through a culmination of disappointments, including: the sudden and untimely death of her good friend and Freedom Farm manager, Joe Harris; her own frequent hospital visits, or the cancerous lump she had discovered in her left breast, but ignored - by her late fifties, Fannie Lou Hamer sensed the end was near. In the early winter months of 1977, she was admitted to the Tufts-Delta Community Health Center in Mound Bayou for the last time. She was being treated for complications related to heart disease, diabetes and breast cancer. Sadly, the steady stream of visitors that had consistently knocked on her door or pleaded for her help or advice had slowed to a trickle as her health continued to fail. Her husband, Pap, lamented that the only way he could get people to come and visit his ailing wife was if he paid them. And he had no money to do that having lost his job with Head Start when the federal operation downsized its outreach in the Mississippi Delta.Hamer’s friends and family remembered how she grew increasingly agitated as her condition worsened. June Johnson, the young woman who was jailed and beaten in Winona with Hamer when she was 15-year-old in 1963 - visited frequently and sometimes found her dear friend in tears and at other times in a confused mental state. During one visit, Johnson recalled how Hamer had sent for a neighbor to come help comb her hair and hours had gone by - and no one showed to help her. Johnson comforted Hamer by gently combing and setting her friend’s now thinning strands of hair. Both Johnson and Measure for Measure leader, Martha Smith, knew Hamer would not live much longer. In a letter she wrote to Hamer’s “friends, brothers and sisters,” Johnson sounded the alarm that Hamer was “seriously ill with cancer.” Johnson pleaded for them to come to Hamer’s “bedside, or send cards, letters and donations” for her “medical expenses” and to support her children. Smith, who had also visited Hamer in Mound Bayou in early March 1977, penned an emergency memorandum to Measure for Measure supporters, who for years had come to Hamer’s aid in helping the poor within the Delta community. Smith likewise appealed for funds to help with Hamer’s mounting medical bills and family responsibilities. Within her memo, Smith expressed how “very hard” it was for her to “see such a strong, generous, and idealistic woman lying helpless, hopeless, broken and broke.” “If you feel you can help out with this crying and urgent need please send a check to Measure for Measure - earmarked the Fannie Lou Hamer Fund,” Smith wrote. But before Smith’s urgent plea for help could ever reach the mailboxes of Measure for Measure supporters, Fannie Lou Hamer was gone. According to her death certificate, Fannie Lou Hamer died at 5 pm, on Monday, March 14, 1977. She was 59-years-old. - Content taken from Fannie Lou Hamer: America’s Freedom Fighting Woman written by Dr. Maegan Parker Brooks The Delta Democrat Times, March 15, 1977. All news clippings courtesy of Bryan Davis and The Delta Democrat.

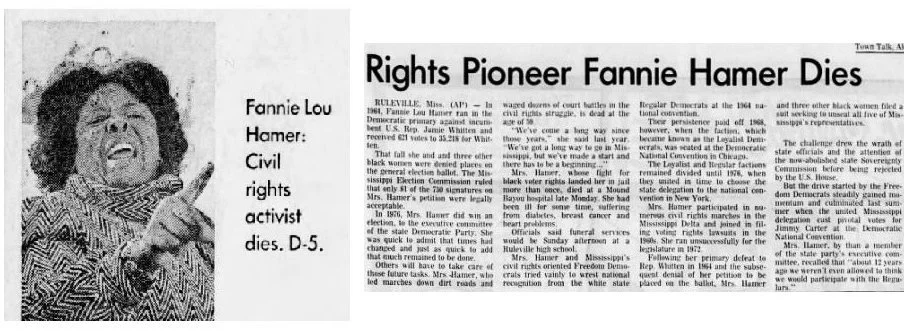

The Tampa Tribune, March 16, 1977.

The Town Talk, March 16, 1977

The Courier Journal, March 17, 1977

“Mac, don’t let them bury me on a plantation.”

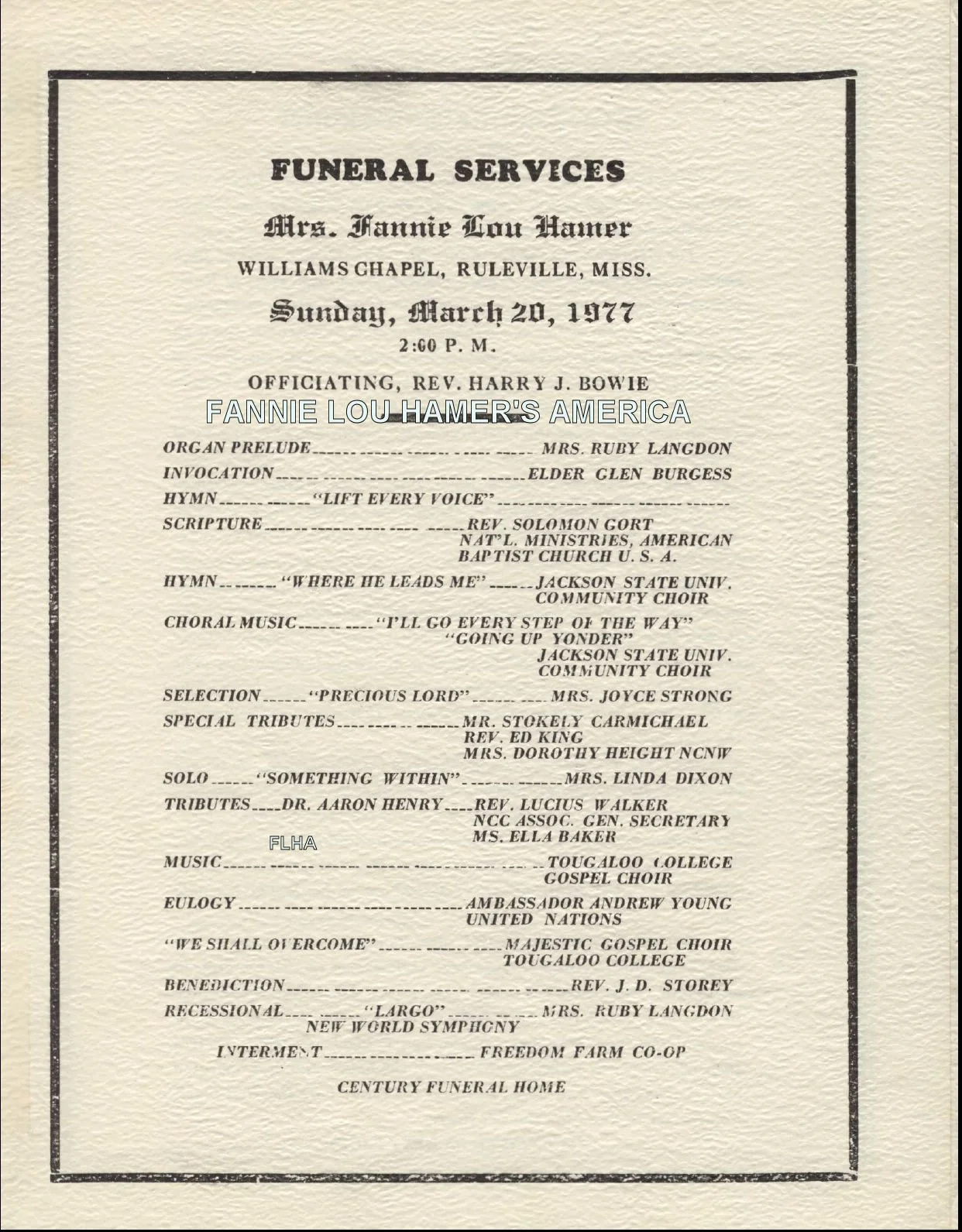

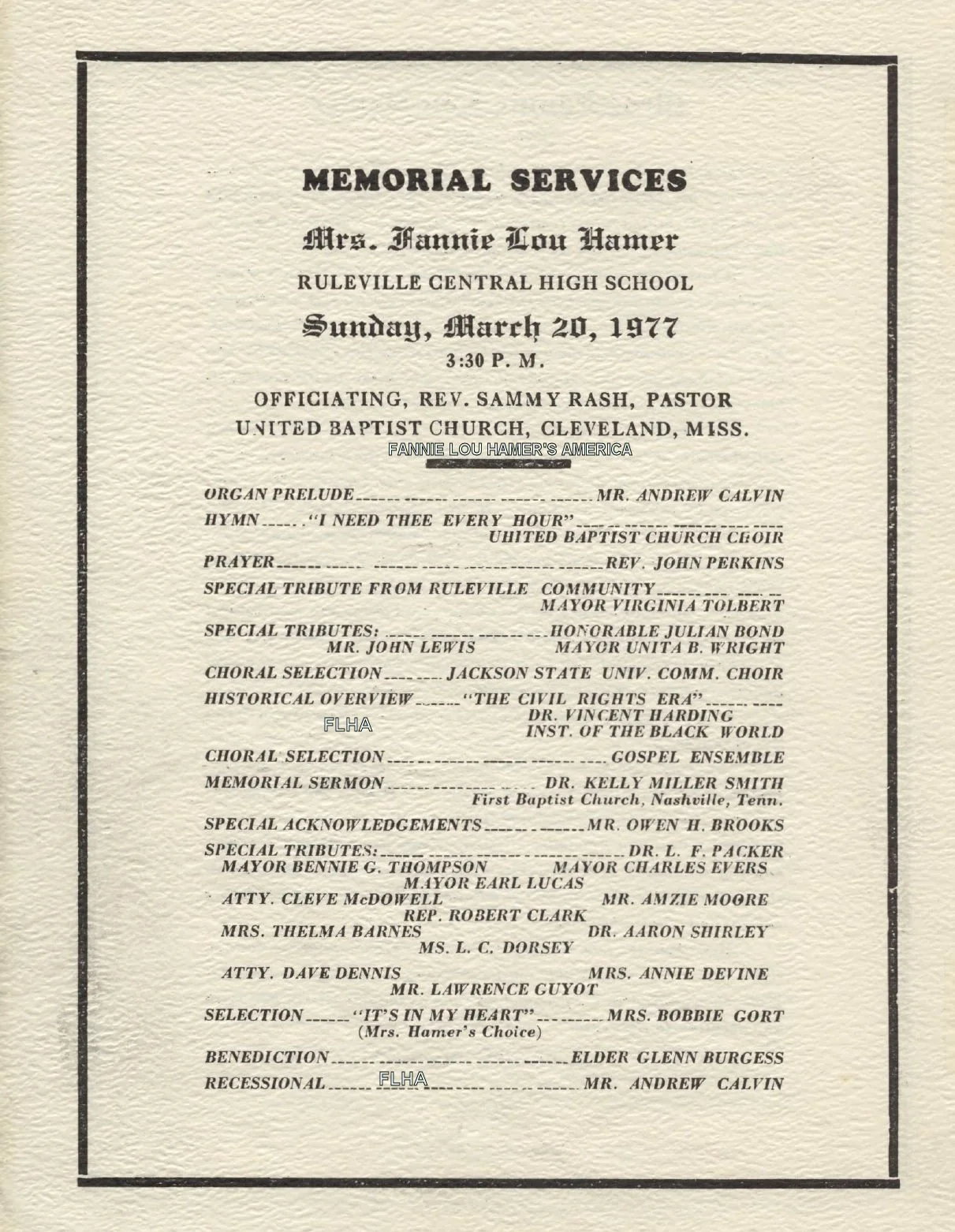

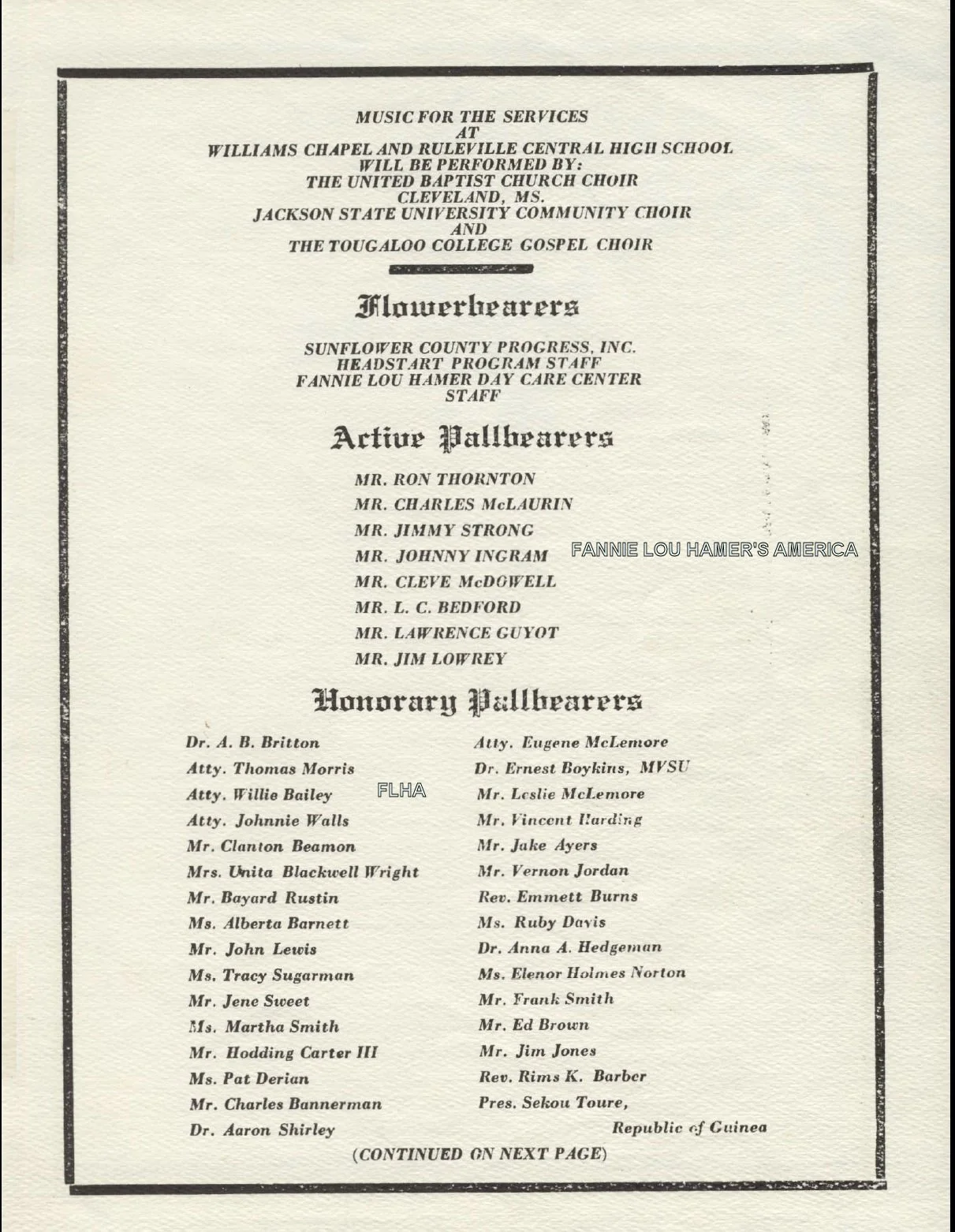

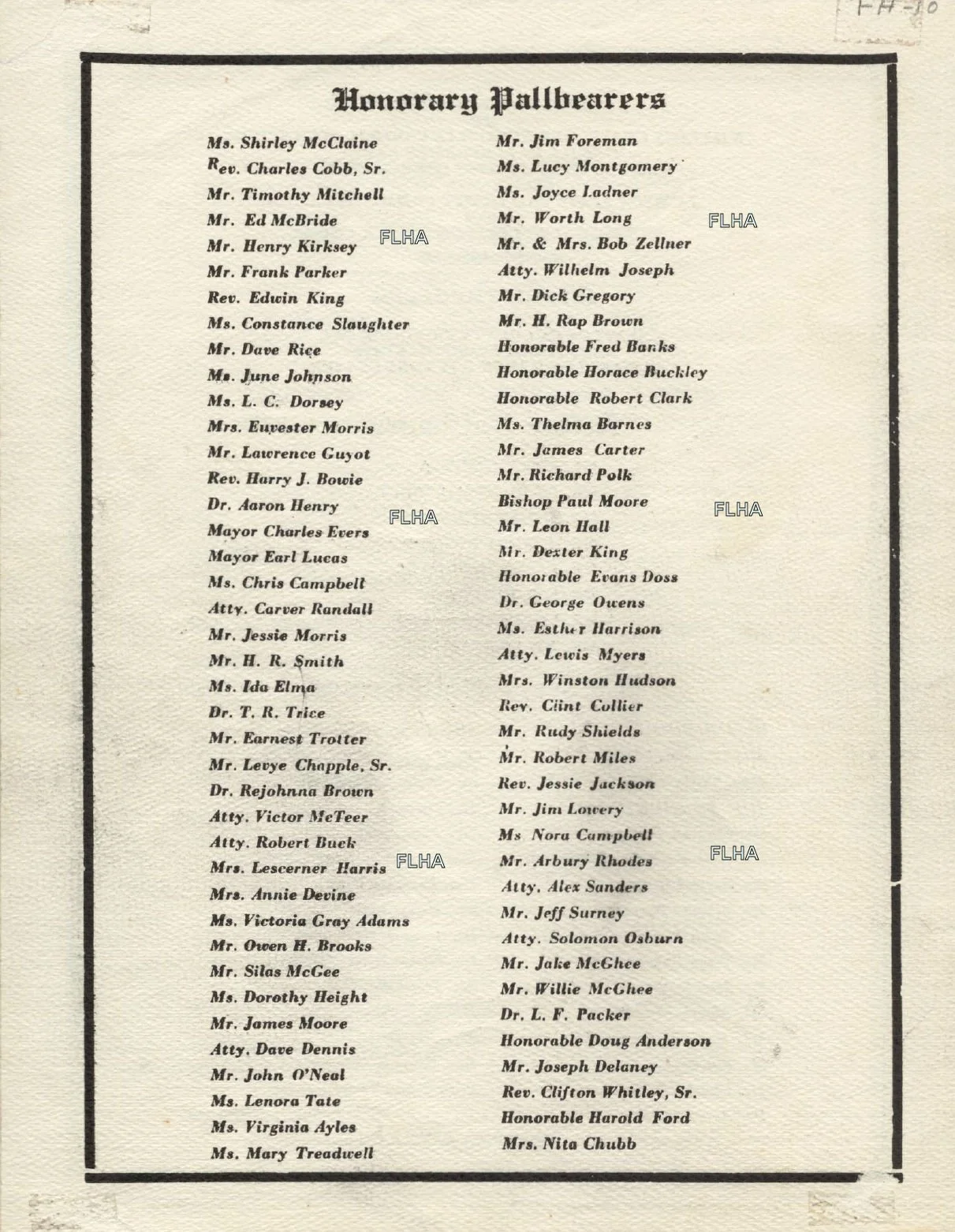

Sunday, March 20, 1977

Courtesy of Laura Heller and the Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer Collection (T/012), Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection, MDAH.

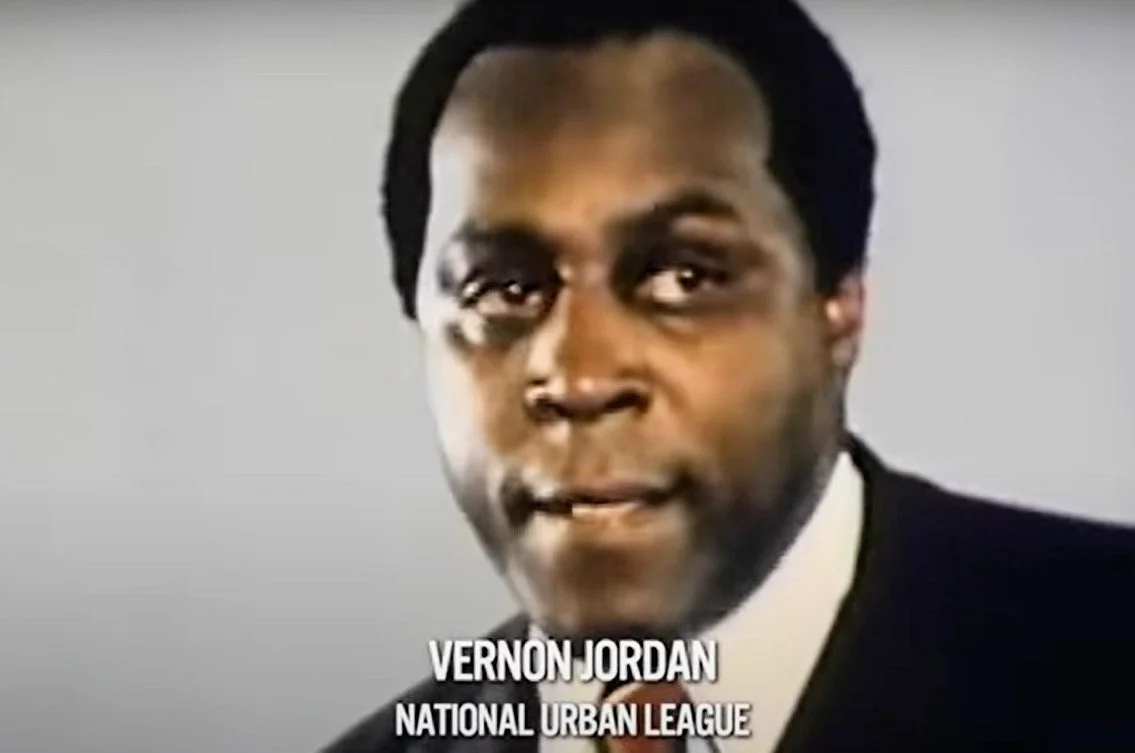

Fulfilling the deathbed promise he made to his beloved friend was no easy task for Charles McLaurin. Still in disbelief over Hamer’s death, he had spent the last week struggling to secure a place for her burial. “I thought about Mt. Galilee, but that’s on a plantation. Then I thought about out here east of Ruleville, it’s on a plantation. See, she knew something I didn’t know,” McLaurin said. “She knew the only places to be buried were on a plantation!”Funeral services for Fannie Lou Hamer were held at Ruleville Central High School and William Chapel Church on Sunday, March 20, 1977. The crowd that swelled into the small rural town more than doubled the 2,500 residents. The three-hour service became a who’s who of prominent Black leaders. Many of Hamer’s fellow activists and supporters came to speak and pay their respects. Among them: Dorothy Height, Ella Baker, Stokely Carmichael, Vernon Jordan, Julian Bond and Andrew Young. The service ran so long, there was little daylight left to lay Hamer to rest. So, the next day, a much smaller crowd gathered in the large, open field between Center and Byron Streets in Ruleville - the last 40 acres of land Fannie Lou Hamer had purchased with donations from northern donors.Charles McLaurin had thought of the Freedom Farms land and after working tirelessly with city officials on zoning - because a body could not be buried on private land within the city limits - a suitable location had been found. The agreement, however, came with the stipulation that a monument to Fannie Lou Hamer would have to be erected on the property within three years, or her grave would have to be moved. McLaurin agreed. Unfortunately, within three years, the statue had not been built. And what’s worse, the bronze plaque and Hamer’s tombstone were stolen, and the site had been vandalized. A permanent monument and statue now stand in what is the Fannie Lou Hamer Memorial Garden. Hamer and her husband, Pap are buried there. “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Ambassador Andrew Young eulogizes Fannie Lou Hamer

Outside William Chapel Church

William Hodding Carter III, Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs under President Jimmy Carter, fought back tears as he spoke of Fannie Lou Hamer.

Vernon Jordan said Hamer left us an "irrevocable legacy of service, of commitment, of sacrifice and of love."

Perry "Pap" Hamer and his daughter Linnie, whom Fannie Lou helped raise.

A crowd gathers in William Chapel Church including future journalist and broadcaster, Callie Crossley (yellow sweater).

(2nd left to right) John Hamer Jr, (Pap's brother); Vergie Ree, (Pap and Fannie Lou's daughter), a young girl, Linnie, (Pap's daughter), Pap and his sister, Willie Ann Mays.

Fannie Lou Hamer's final ride

JET Magazine, April 7, 1977